|

| Riding into Amboro |

|

| Heading to Padilla, a house along the way. |

I’m walking now, in a town called Padilla. The streets are broad and dusty. An iron fence surrounds the large tree-shaded plaza and there’s a man leaning against it. He turns his face towards me as I stand deciding where to go and I notice his leather hat. It has a broad peak and is the colour of red mud. The colour matches his own skin. In the shadow cast by the hat, I see his two eyes glowing white as light and a warm friendly grin shines out as well. It’s the only smile I receive here in Padilla though as the other men, sitting in plastic chairs lining the avenues, are drunk and drinking….and staring. I don’t like the stares, even knowing they are purely drunk inquisition, and I feel a little uncomfortable. The women appear tired. Tired of the men perhaps and they pay me little attention as they walk with heads that hang like so much weight, feet dragging in the dust. And so, as the men drink and the women amble, it is the children who are left to manage the shops; selling wine, beer and cigarettes to the inebriated men. So strange, to allow so many days of so much sin for the whole of Holy Week. Thanks be to God. And to Jesus who died for our sins. Would it not be better if we died for our own?

My footsteps echo as I walk down the narrow passage hemmed-in between white walls. It leads to the town’s market and inside, tucked into one corner, a solitary woman at work making neat pyramids out of purple, red and orange. There are sacks of green and the smell of earth; that metallic tinge of freshly pulled potatoes, and on the floor lies a baby, kicking its legs on a colourful cloth. The woman smiles and the baby too, making three smiles in Padilla. Despite struggles with baby, the woman counts apples and tomatoes into a bag for me and then goes back to busily preparing her vegetables, expecting an imminent rush. Then, as I walk further, back on the pale avenues now and looking for bread, the stares are glares like many hands, kneading me small.

|

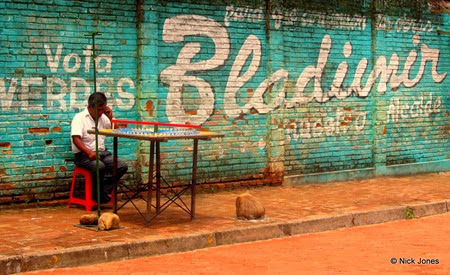

| Another man hunts for the feast in Villa Serrano |

Villa Serrano, a short ride away along smooth red dirt is in complete contrast with Padilla. The exception though is that still everyone is drunk. Thankfully however, they are smiling and quickly I lose count of just how many smiles I receive. Even before I’ve stepped from the bike an excited man hurries to tell of a huge feast to which I must go for a belt-tearing lunch. I’m beyond hungry, it’s late and the afternoon hot. I sweat and sweat as I walk and walk in search of the fiesta, expecting and hoping to stumble upon the great and noisy feast. I look out for open doors and listen for the familiar tinkling of cutlery on china, or for people returning home holding taught bellies, sighing and grinning with over-fed satisfaction. But, I find none.

Exasperated and hungry I return to a shop beside the main square. There’s a metal gate in the doorway and I whistle into the dark interior. Feet shuffle, and from the wood and shadows comes a friendly woman who brings me a coke and the last of some old looking empanadas. I take these to the park together with some green mangoes bought from a nearby truck-full. Famished and parched I bite into the empanadas, the old cheese cracks between my teeth like plastic. Children come over giggling nervously to practise English as I struggle to quickly swallow the dry pastry in my mouth, “My name is Angelique. What. is. your. name?” With my mouth still half full I reply, “My. name. is. Nick. Nice. to. meet. you!” Angelique looks at her friend, let’s out a shrill and they run off giggling all the way across the plaza. Tired from a long morning’s ride and as such content, I sit there enjoying the time, the place, the mood, to just be and watch. Then a boy trips and falls on his face and cries and cries, the moment is broken and I return to the bike.

“You have been to see Che! [Guevara]” asks a man as I reach the bike.

”No, I’I’m going there now! I’ve just come from Padilla.”

”Ah, okay….so you go this way?” he says pointing up the hill.

”Hm, actually I don’t know, is it that way?”

The whole family begin describing the route in great detail, each one confusing me with little titbits of information,

“There’s that tree….” says the first.

”And that big hill….” says the second.

”And then the bridge.” says the third.

”but you don’t want to take the right…” says one of them.

”oh, no!” says another.

”The right?”

”You know if you go right mi amor, it brings you out on the opposite side of the river,”

”no that’s the turning after the house….”

”no that’s the left before the bridge, I’m talking about the right AFTER the bridge?”

”What bridge?”

And so on until perplexed.

But soon, with their legs buckling under laden stomachs they succumb to sitting on a bench with sighs of relief, the directions stop, legs outstretch. I tuck the last of the hard empenadas into the top-box and as we talk it’s not very long before the family are inviting me over to their house to eat their Easter leftovers, “I made too much,” says the mother, “we’ll never eat it!” I contemplate squeezing in a second lunch but also the very preposterous notion of rejecting a good meal. I hang my head and admit that, no, sorry, I’m simply too full to eat any more and I have to decline! Before I have contemplated this too long they turn the conversation to ask more about my travels.

“So where do you wash?”

”Rivers usually, pools, the sea….” [not a boast, I’m just tight]

”Que hombre!” (not true)

“No, well, actually it’s a bit tricky here [in Bolivia], the altiplano is so dry and cold, not many rivers!”

”So, when did you last wash…”

”Hmmm….about one week ago, outside of Tarija, a very nice river!” With really big tadpoles I remember.

”You can take a shower at our place if you like?” the daughter says. I think about my feet, they are awful, smelly.

”Nooo…really, thanks, it’s okay. They’ll be rivers ahead, it’s no problem…I don’t like to be any trouble.”

”Ah don’t worry it’s okay!”

”Well,” says the son-in-law, “you’ll be able to wash in the Rio Grande ahead!”

We laugh, because it’s obvious that I won’t of course. We continue to talk for a long time, though I can’t concentrate on what is being said. Instead I find myself wondering why it is that I have turned down all these fine offers. But I know why. And my smelly feet are just one reason.

Leaving Villa Serrano I kick myself for turning down the one thing I’d have hoped for on Easter; Sunday lunch with a friendly family. I pass by the mango man at his truck on my way out of town with a nod, and as I continue along open roads I begin to analyse things past. What was the problem, why did I turn down a free lunch? I can’t leave a problem unsolved, there has to be an answer. It leads me to wonder why do I do what I do, and why do people do what they do. I treat people (and myself) like a problem to be solved, trying to work them out, to find the answer, and once I have the answer I’ll be on to the next one. Or else I can’t solve it and will move on anyway, will leave it behind, fearing the problem, my problem, me. Until I forget the people, the laughs, the beauty, moments of connection until all I can remember is the problems.

As I ride, finding it hard to leave the questions behind, eventually the way has me concentrating and enjoying. The road stops, disappearing into a muddy river which only barely slides by. There are two tire ruts cut deeply into dark wet sand leading into it . It’s a small river but it looks very soft and I fear getting helplessly stuck in the deeper sand in the middle, but I’ve little choice. Across I go, wincing, fearing the saturated sand, but this time Rodney manages to pull through. I puff my cheeks with relief as I exit and continue along, up and into airy pine forests. I love pine forests, love the cool air, the soft warm floor of orange needles, the enchanted feeling, the husssssh of the wind through the trees. I think about camping here until I see the route ahead, zig-zagging down into a triangular valley and boxed in at both ends. Perhaps just a bit more then! Soon though and I remember back to the Pilcomayo canyon where it was so hot in the valley floor, up to 55°C! Whilst not wanting to hit the higher heat 2000m lower, I remember that I have no water for camp and no fuel until distant Samaipata meaning I’ve little option now but to continue onwards, downwards.

Reaching the Rio Grande and there certainly isn’t an opportunity to wash. The river runs black and angry amongst a mass of huge jagged boulders. I can only imagine the carnage which the rain must bring. Without my old Katadyn water-filter (broken, I’ve only a – crap -Steripen now) the water is undrinkable and I’m forced to back-track a short way to a few shacks. I park up outside the fencing and whistle out towards the buildings and a solitary pair of bare feet which I see pointing skywards at the end of a bunk-bed. The guard comes out, chats, takes my bottles and – glad for something to do – fills them up from his own supply which he probably filters and boils himself. He has the unenviable job of watching over some mango crops and works 30 days on and 30 off. No books, papers, TV or friends, just mangoes. And the odd (as in occasional) gringo.

Down down goes the road and looking back it’s hard to spot the way I’ve descended, just sheer green walls on all sides, I’m surrounded. The steep road provides no opportunities to camp and the few houses I find are deserted with no one to ask; locked up for Easter. Eventually I find a section of old road where a landslide has left a smooth lick of black lava-like dirt. Having taken the trees with it, this landslide area also gives out to a fine uninterrupted view down the valley, all the way to the glittering Rio Grande snaking still farther below. A fine spot!

|

| Parakeets, kwok kwok kwok! Nice noisy comany |

Around the far side, noisily singing amongst the remaining trees are parakeets. I leave the half prepared tent to walk along a narrow uneven path amongst the debris of the landslide to get a closer look. I see swarms of the parakeets then, sweeping up and down, pausing occasionally and filling the trees with flecks of luminous green and red. I inspect how much foot traffic might still be using this section of road – in case I should expect company – not much, and none recent. As I finish preparing the tent I see, passing above me on the mountain ridge, the slumped shoulders of an arriero and the bobbing neck of his tired mule and I wave. The sun sets, grey and purple and I stand admiring the view, excellent. Then I kick myself for not accepting the Easter lunch. Stupid. Utter silence then, no traffic, and for tonight the valley is mine, o mine.

|

| Camp, Rio Grande in the distance |

By morning the parakeets have gone and the cool mist brushes over me as it reaches out from the valley towards the rising sun. I sit and read and read and by the time I finally jump into the motorcycle’s saddle it is scorching hot in the late morning sun. I’m alone on the road and ride slowly downwards into the valley, content, looking out from the road to the Palo Blanco trees with their small yellow buds like buttercups popping out on their pale, leafless and papery branches. As the ride progresses and I near my destination, La Higuera, I start to wonder about the route, and the man behind it, it’s called “La Ruta de Che”. I know little about Che Guevara and I wonder how many people really know much about him, save for the image on a T-shirt and the fact that he rode around South America on a motorcycle. I was hoping to find out more.

|

|

|

I reach La Higuera and talk with three men who are thick as stumps. They’re drunk as Holy Week continues but they’re very friendly despite the obvious tourist trade visiting this tiny village. They sit on worn wooden chairs, painted light blue, and lean back against adobe walls thinking “here’s another one.” On the floor are slim glass bottles of liquor and on top of the heavy brown walls lie the familiar green plastic bags of coca leaves for chewing. Together with the leaves is also a crumbly silver powder that acts as a catalyst for the coca chemicals, perhaps ash of quinoa. I don’t ask for a picture, though I want one of this popular habit. Instead, shy, I move off to a museum which is set up in a small bland adobe building. The museum, not much bigger than my tent, is probably a bit crap. But then at only 90p ($1.50) I’m going in anyway.

Inside, it is a long and thin room, like a big coffin. There are some photos, a military green jump suit, like Che’s though not his and a calendar of events in Che’s life. One wall is almost completely covered with contemporary notes thanking Che for his example, his commitment, his inspiration, and his sacrifice to “the cause” or “freedom”.

“They were caught here,” says the curator pointing to a map of the valley, “they were spotted by a peasant when stealing his potatoes.”

”Ahh, right.” I say, not really sure about Che’s story, what has Bolivia got to do with him?

”They had very little to eat. The peasant told the military that the guerrilla were here and the army came and cornered them in the valley. Then he was brought here.”

I carry on reading.

“That’s where Che was shot.” says the woman.

”What, here!?” I ask dumbstruck.

”Yes, he was sitting here and asked to go here. He was shot nine times, by the Bolivian Army, in the legs and throat.”

”Nine times!”

It seems hard to believe, not that it’s unbelievable, but instead simply incredible that here, right here, is where Che was shot.

|

| Ché was shot right here |

“They [the CIA and Bolivian Army] wanted it to look like he was killed in action,” continues the curator, “after he was shot, they took his body to Valle Grande,” a town nearby. I don’t understand some of what she says then, but gather something about his hands being cut off and his body being thrown in the woods.

The photos depict a man almost completely unlike Che, certainly of little resemblance to the guy on the T-shirts, save the hard dark eyes. I’d have to read and find out more about him I thought, and over the coming evenings and mornings whilst sat at camp I did just that.

The full story of Ché’s life is long and quite extraordinary, despite its relative brevity. His Cuban nickname was Ché – coming from the Argentine tendency of using the word Che like the British say “mate”. His actual name was Ernesto Guevara. Travelling South America Che’s eyes were opened to the exploitation of his continent by the north Americans. With a growing interest in socialism/Marxism/Communism, Che ended up in Guatemala for the sole purpose of bearing witness to the country’s revolution. It was there in Guatemala that Che’s opinions of the north were solidified, as he saw the CIA-backed (in conjunction with United Fruit Co) guerilla forces overthrow the socialist president Arbenz (who was at the time carrying out land reforms to hand land owned by UFC back to the Guatemalan people, hence the name you may have heard, The Banana Wars and probably also, Banana Republic). Later Che fled to Mexico city, where he first met with Fidel Castro. It was the beginning of Che’s rise to fame, both with the public and the CIA. Together with Fidel, Che trained, planned and – despite his non-Cuban status – became an important part of the guerilla force planning to invade Cuba to over-throw the dictatorial government. On 2nd December, 1956, Che and Fidel together with just 85 others landed on Cuba’s beaches as a guerilla force. After three days march, Fidel’s forces were attacked by President Batista’s – CIA assisted – Governmental Army. (Later the CIA’s funding was ceased when they realised that actually Batista was a murderous dictator (hence Castro’s invasion)). Of the 87, only 22 (or twelve depending on sources) survived the initial skirmish. The rest of course is history; these 22 (or 12) somehow successfully destroyed Batista’s army, over-threw the government and by January 8th 1959, both Fidel and Che had arrived in Cuba’s capital, Havana.

Some time later and with Ché hoping to spread communism further, he left in search of the next revolution; the DRC (then Zaire) in Africa. Ché however, eventually gave up his fight here, thanks mainly to lazy, drunken Congolese colleagues. He returned to Cuba and planned his next mission; to rid South America completely of “gringos”. His plan was to start in Bolivia, rather than his homeland of Argentina. With Bolivia bordering five countries, he felt it would better facilitate the spreading of communism, on all sides. But unlike in Cuba, where the locals were quick to help, the Bolivian people seemed apathetic. Unable to see further than the next meal or fiesta (perhaps) and hoping for a quick fix, the Bolivian people were easily bribed by – CIA assisted -governmental forces, paid into informing and double-crossing Ché at every step. It meant that Ché walked into one ambush after another.

As the situation worsened, running out of food, they turned to stealing and in one particular instance were spotted by a farmer as they stole his crop of potatoes. The military soon arrived again, this time shooting Ché three times, catching once his rifle barrel, piercing his calf muscle and then – more to his chagrin – his famed beret. He was taken to the village school in La Higuera – now home of the museum where I am – and there the military awaited instructions. The order soon came from the Bolivian president to kill Che, relayed by Felix Rodriguez (a CIA official at the scene), who instructed the Bolivian army to make it appear as if Che had been killed in action. Asking for volunteers, a drunk militiaman named Teran stepped up to avenge his three dead peers. The CIA official, Rodriguez stood outside, heard shots at 1:10pm and walked off to make notes.

Ché’s was shot nine times on October 9th, 1967, he was 39. His body, first displayed in Valle Grande was later tossed, without his hands, somewhere into the woods. The body wasn’t discovered until 30 years later, in 1997. Exhumed, he was then taken not to his homeland Argentina, but Cuba, where he now rests (though probably not in peace, as it must pain him that some capitalist bastards are making a fortune from selling t-shirts made in China and worn by gringos!). Other points worthy of note, Che was a phenomenal writer, a nasty murderer, about as far left-wing as Kim Jong-il and to top it all; he never actually rode a motorcycle around South America.

As I leave the museum I read in the doorway, “By this door left a man to eternity.”

As I leave the museum I read in the doorway, “By this door left a man to eternity.”

Myself? Well, I’m off to a place called Samaipata. I take a route as advised by a Frenchman who I also met in La Higuera, he was a friendly guy but I got the impression that he more or less lives a life of lazy drugged debauchery, inviting travelling Che fans to sit, drink a beer, smoke and eat munchies. On the other side of the road his father runs the the only other hostal; the Telegrafista Hostal. So the family have a nice monopoly on the tourist trade there. Something else to please Che! Que mierde!

|

| Alberto Korda’s famous picture that made a million shirts. |

The Frenchman’s recommended route is tricky to find, though this in part due to everyone that I ask for directions being a tad tipsy for Easter. Up and down the road I go again and again, looking for the turning. I stop as a man tosses a red snake into the road and watching it land with a flat splat I see that there are three other snakes in the road too, red and dead. The man is slicing his way through the tall grass of his garden with a machete. When I ask the way, he simply points with his chin to a younger man nearby, “ask him.” Without so much as a second glance the man returns to his work, preoccupied I suppose with red snakes. I’m told by the second man that I must turn off a little way back, at the school. I saw no school but take him at his word and when I return again the school seems obvious and huge. A road doubles back behind the building and then, sweeping around gently, the red trail crosses the valley plain directly towards a sharp green ridge of mountains. I hope to find camp away from the village somewhere in the mountains but when I get there I find that there is not a single opportunity to leave the road. After crossing the mountain pass, I drop down the other side into a second winding and fertile valley and with still no chance of camp, I continue onwards, zigging and zagging tiresomely up a second towering mountain ridge. Finally, a little exasperated and approaching the top beyond the tree line, I find a great spot and thankfully start to set up thinking of nothing but a thirst-quenching brew.

|

| Continuing to Samaipata |

|

| Entering Pucara, I think |

Slap slap slap go their feet on the hard pack. Heavy feet filled with drunkenness, finishing work for the day and leaving the fields, talking loudly of the night ahead at the Easter fiestas. Whilst the drunk men pass nearby on both sides, luckily they seem not to see me and once the sun sets I have a quiet night. With the only noise being the sound of spoon on pot as I eat hot veggie soup, I look off to the distance, towards the first mountain ridge which stands out black against a moonlit sky.

|

| Camp, looking back over the day’s ride and the distant ridge, itself beyond many ridges and beneath the cloud! |

The cloud, warmed by the rising sun tumbles heavy and plump over the same distant mountain ridge in the morning. By midday, I’ve ridden down from camp and into a third valley which I follow north to reach the main paved road to Samaipata. As a Sunday, Samaipata is busy and it’s obviously a popular town for both foreign tourists and local weekenders from nearby Santa Cruz. These people in trendy clothes come and go on quad and motocross bikes and fill the street tables of cafes surrounding the plaza and actually there seem to be few genuine locals. I don’t eat out very often, mainly for budget, but today – perhaps to make up for my lack of Easter lunch – I decide to eat out! As much as I yearn for one of the chunky burgers and chips on offer, I force myself to find something somewhat authentic and by luck I find a really great place. Here the cooks are grandmothers and mothers, the waiters and waitresses are the children, and the owner is a mafia-don-like Godfather. I get the very last of the day’s Easter special meals; a huge serving of chicken, rice and salad. All this is served with a drink of mocochichi, a juice drink made with dried peaches, each glass with a big peach-pit. Sat in a plastic patio chair, as is quite common, I sit contentedly eating, listening to the coming and going of people, and the happy party talk of the large Latin families.

|

| Juan, top man! |

The hills of Samaipata are a lush green of perfectly trimmed lawns dotted with exceptionally fine houses. These houses are European in style, clean and neat, the archetypal chalet retreat in the forest, away from the city. By Monday almost all of these houses – immense by Bolivian standards – are unoccupied, save a gardener who ambles about the large gardens and pools. All that effort, a perfect house, and no one living there! I stay in a hostal and the owner, a crazy teacher called Juan, gives me a tour of the town and -more so- its surrounding houses, “LOOK!” HERE’s ANOTHER $45,000!” he says in complete disbelief as if we’ve unexpectedly stepped upon a gold mine, then instantly, “LOOK, HERE’S ANOTHER! $40,000!” I don’t have $40,000 I think, but these houses are massive and I could easily make do with a much smaller place (for $4000)…and without a gardener. Back to the hostal and it’s coffee time with Juan, his wife and the hostal’s housemaid (oddly I was the only guest). Juan likes nothing better than smutty jokes and innuendo and whilst it’s obvious his jokes have been told a thousand times over, we all have a very good laugh together, Juan especially. Juan decides that he wants to buy my bike, as for him – and all other Bolivians – genuine Japanese bikes are hard to find and expensive with the market instead being dominated by cheap Chinese copies. I like Juan and right here I change my trip plans, promising him that once I reach Ushuaia I’ll ride back to Bolivia when he can buy the bike.

“But let me buy it now!” he says,

“I kind of need it, Juan!”

“Just take the plane!!” he retorts.

|

| Hunting for lunch, Samaipata |

The charm of Samaipata is its cool fresh tranquillity, away from the humid bustle and smoke of the city and yet not as chilly as the barren altiplano. I find it hard to stop in one place any amount of time, worrying as I do about costs, even in economical Bolivia, but so friendly and comfortable is it at Juan’s that I decide to stick around a few days and catch up on laundry and bike maintenance. Juan goes to work at the school early in the morning, looking comically serious in shirt and tie as I recall the jokes he was telling last night. As the only guest I’m left free to work in the hostal’s cosy tiled courtyard. I chat with the maid as she launders sheets and clothes in one “pila” and I launder my own disastrous rags in another. The large red parrot chirps in occasionally as we work and watch the “tele novellas” (Latin soaps) on an old black and white TV set.

My laundry finished and hanging next to the parrot under the eaves, rain starts to pour down making the tiles of the courtyard slippery. Famished as always, I leave for the market, scampering down the streets as the rain fills potholes and gutters. I see a dog poo wrapped in plastic as tight as a sausage skin; the dog had literally eaten a bag of litter, nutrients zero. Into the market then, a dark and morbid place, all shade and shadows, but dry at least. Past the first stalls selling crap, Chinese who-knows-what crap, past three children playing in the bloody black muck of the market floor. Bowls of bowels on a chair, offal and hooves and cow hide and heads. Out towards the far end of the market where there is fruit and veg, more open here, colour and light.

|

| Courtyard of the lovely hostal |

“Why do you always buy from her!” hawk the other ladies, or tut as I buy my daily rations. “Because she smiles!” I say over my shoulder with a grin. And she does, seeming happy for my custom, my few pence, though she seems anxious too, I fear. I see a dog rather happily trotting out, the plastic dog-poo dog perhaps. The dog holds his chin high; to save snagging the long furry cow’s leg and hoof he carries in his mouth. Bread I need then, the bakery I know is on the edge of town, difficult to find the shop once, harder still a second time. I find it finally and sniff at the door, it seems cooler than usual and there’s a distinct lack of bready odour. I whistle and the woman comes out smiling and slapping her hands clean on her apron, “mas tarde!” she says with a smile recognition. I’ll go back later.

I hadn’t needed the bread. Juan provides plenty with another round of sweet black coffee in his kitchen. In between his laddish jokes I talk to him about my route ahead. Whilst I haven’t made any plans from here, I’d noticed several tour companies offering trips to Amboró national park and I ask Juan about it. Juan can’t tell me too much though, only that there are toucans and that the jaguars take a particular fancy to green tents and “gringitos como te!” “Me! But why? There is no meat, I’m so skinny!”

|

| Heading to Amboró |

The next day I ride away from Juan heading to Amboró, promising to see him again in March and sell him my bike. Whilst it had crossed my mind some time ago, only now travelling on the wet and muddy road to the park do I realise that I’ve been travelling too slowly and the rainy season has begun. I’d only expected to spend a month in comparatively small Bolivia but it’s been two months already and I’m certainly not ready to leave yet. But it’s not just here I’m a little anxious about, but also Ushuaia, which I must reach before the winter, during which time I’m told the roads will be impassable.

Amboró has two sides, a lowland north and an elevated south entrance, separated by a less visited central area. It’s possible to actually cross the whole park by foot over two weeks. There is even talk of a road being cut straight through the park in the future to speed up exports from the lower jungle farther to the east, which currently have to travel to the distant Brazilian ports rather than cross the Andes by circuitous routes to the actually closer Peruvian ports. This is actually a bone of content amongst Bolivians and Chileans, as Bolivia lost its seaports in a war against Chile. The pact was agreed similar to that of the Panama canal, a one hundred year lease, only the hundred years ended five years ago. Chile would lose two large cities, key ports, its border with Peru and a vast area of mineral rich altiplano. (Don’t take my word for any of this, this is just what I was told and has no citations).

I’m travelling to the southern entrance of Amboro which, as well as being closer to Samaipata, also contains the majority of the birdlife, in an area called “Los Volcanes.” The trail is a variety of muds; hard-packed red clay, sandy dust or loamy soil and is either dry, saturated, or else a steep glassy sheen of solid clay that has just a sprinkling of water making it slippery as a toad.

|

| Burrowing through the jungle to Amboró |

As I round a cliff top, several large parrots fly by in pairs, dipping amongst the trees and across my path. I leave the bike to walk in hopes of a closer glimpse, camera ready. They are turquoise, white and orange with black faces, and I call them “panda parrots” for I feel sure they have white ringed eyes, but now in memory that seems a bit absurd. In any case, they are skittish and fly off always just out of view until finally, tired of my hunting they drop down into the immense valley. Turning to watch their flight – and curse the buggers – I then notice the tombstone-like red “volcanes” rising up steeply from the valley floor and supporting the low rain clouds.

|

| Los Volcanes |

|

| Los volcanes |

Back on the bike and snaking along the top of the ridge, the road forks off left, angling down the steep sides. It could be too steep for my bike to climb back up, especially in the wet and certainly if rain continues overnight and I worry about becoming stuck in the valley. For now it’s fun, tunnelling through the dark green of the jungle on thick and loamy wet soil and mud and bridges. I pop out then into bright light and a large neatly trimmed lawn surrounding the national park lodge. However, when I speak with the staff I find that camping is not permitted and the rooms are by reservation only. I try to explain to the staff, that I need just a small square, perhaps 0.5% of their space for my tent. Understandably they hold their ground. They point and I follow their outstretched arms to behold; the high mountains down which I’ve just descended as unmoving as their unbending rules. I sigh. I get back on the bike as a small jeep pops out from the trees at the base of the mountain and crosses the grass to disgorge another group of brightly coloured smileless reservees. Pricks every one. Though perhaps I was just a bit envious.

|

| STEEP! Dropping down to the refuge…hope it doesn’t rain. Spot the bike. |

In the saddle again, away from them, up the hill, a bit of clutch, lots of revs and actually the bike makes it up better than I’d anticipated, which is to say it made it up. When I reach back to the fork in the road I turn left to continue onwards around the high ridge above the Volcanes valley on new ground, deeper into the park. This road doesn’t appear on my map, but I know that I’m heading roughly north east and I wonder if I might actually be able to cross the national park by some secret road, this road. I pass one or two small farms as I rise and fall, skirting just beneath the peak of the spiney ridge until I come to a lofty and abandoned refuge. The refuge resembles a research centre from Jurassic Park, torn apart by a T-rex! It has a very commanding position, looking far, far out to the north across a vast plain of unspoilt jungle. The road becomes very feint here and unsure where it goes I decide first to ride back to where I spotted two men working on a telephone mast and ask them about it.

As well as the two workmen is a family that actually live in the concrete shelter which otherwise houses the electrics of the telemasts. They tell me that this road goes nowhere and now I feel as if I’ve wasted a whole day going nowhere, here in the rain. We continue to talk as a second engineer climbs down the mast and the father looks back to his family huddled apprehensively together in the doorway of the building. We talk about the park, the birds and wildlife and the father assures me that there really are “loads of birds,” and just to prove his point he raises his chin and says “there’s a Great Big titted warbler” or some such. “Where?” we all ask, as not one of us can see it. “There!” he says and the bird warbles again, calling out as if to say, “He-are-he-are!”

Unable then to cross the park by this road I have just one option remaining; to return. Descending a steep pane of slippery smooth hardpack I decide to pull off before reaching the busier main road with its inherent difficulties for finding camp. I leave the road by a thin foot trail through the jungle a short way across angled slopes to an opening and shut out off the engine. It’s later than I’d thought and darkness falls as I set up and with it comes a crescendo of pleasant bird chatter and insect noise. Amongst the noise is the very interesting throaty bark of the “wailing death bird,” which starts off as a blood curdling wail and finishes as a sleepy whistle, “WHAAAA.whaa, wha, whaf, pfoo, pfoooh ….WHAAAA.whaa, wha, whaf, pfoo, pfoooh!” An interesting one that never fails to make me smile despite my nagging fear that if it rains in the night getting down this steep trail tomorrow will probably involve me using the bike as a sled.

|

| Ants come in one size: BIG |

|

| This fella was also big, and digging a hole |

|

| This chap was a little bit bigger than the ants! |

|

| Camp in the jungle, a bit tight, noisy and nice |

Anxiously I leave the tent in the morning, half expecting to find that it has been engulfed by gnarly green roots of the jungle, but it’s not, it’s even dry and Rodney is still there too, though he is going to take some extricating from amongst the trees. Not wanting to give up on Amboro, stubborn fellow, I decide to try and enter the park via its northern entrance. This means a lengthy ride today, all the way around the national park via Santa Cruz to the village of Buena Vista on the park’s northern border.

Despite good paved roads which link Bolivia’s industrial capital Santa Cruz with outlying cities, it takes much longer than anticipated and it’s not until the end of the day that I arrive in Buena Vista, the jumping off point. Wanting to be prepared for tomorrow I rush around the market to stock up and also to replace broken shoelaces. The latter proves a little tricky as I only know the Spanish word for ropes, “cuerdas”. I walk then looking for the national park’s information centre, passing a man sat at a roulette wheel on the pavement waiting for betters and farther up I find the entire populous of school children playing fuzzball at a set of tables actually filling the street. The information centre for Amboro is contained within a small home and a helpful girl concedes that most visits from this side, like the south, are with organised 4×4 tours. Also I can only enter the interior of the park with a guide, but this isn’t the biggest problem as – with this side of the park being more inhabited – I can use local guides. The biggest problem is to actually get there. With the rainy season getting underway, and having had several days of heavy rain the rivers have become impassable and even 4x4s normally carrying the organised groups have been forced to postpone visiting. The silver lining however, is that on the bike I might be able to use a canoe to get across the worst and highest river. Thereafter are several lesser rivers and I’ll have to cross those alone. “Oh, and normally,” the girl continues, “the last section you have to walk, buuuutttt, wait….you’re on a motorcycle, right? Maybe you can make it!” Maybe.

|

| Not many takers at the roulette wheel |

|

| Because everyone is playing fuzzball! |

|

| Riverside camp |

|

| A great moment when you see this view and KNOW with all certainty that, “this is the spot[to camp]!” |

I ask the girl about a good spot to camp for tonight and she gives great advice which leads me far outside the village until I come to a point where the muddy road stops and disappears down into the huge twist of brown river, the Surutu. A large patch of grass here provides a great spot for camp (#527 on map, the river must have moved/widened) and offers a high viewpoint over the river, which looks immense. Whilst I don’t need to cross here I fear that I won’t be able to farther upstream tomorrow. A man arrives then in a taxi, the taxi stops, the man gets out, the taxi leaves, and I ask the man where he’s going, “over there.” he says gesturing to the far side of the river and picking up his bundle.

”What, you live over there?”

”Yeah.”

”But…how? How do you get there?”

”Caminando,” he says.

And sure enough he walks across. Maybe I can cross!

The night is thick black, like the first moments after turning out the lights and you can’t see a single thing. This time however your eyes never adjust and you continue to be blind. Despite its proximity I can’t see the river and can only barely hear it, as if the darkness -like a black hole- is swallowing all, reducing the noise to a muffled hush. My tent is tucked up on a grassy corner between river, road and jungle and with dinner finished I sit in the darkness sipping tea, just observing the darkness which seems new and unique, trying to see or hear something. The birds are quiet now, hiding away in the safety-net of silence amongst the trees for the night, but then I hear something; the unmistakable snarl of a cat. A big cat I think, though I hadn’t heard a single twig break and I wonder if maybe I’m mistaken. Then I hear the noise again, an angry hissing snarl, as if the cat has seen the tent, doesn’t understand it, doesn’t like it. Without a moments thought I reach beside me and put my hand on my head-torch and quietly I get out of the tent. I stand slowly and slip the torch over my head but leave it turned off. It is dark, dark and somewhere, the river hushes by. In my socks, I feel the soft prongs of grass and the cool wetness of the mud seeping into them. I stop, the cat I know, was close. I stare and squeeze my eyes to try and squeeze life into them, to see. But I can’t, I need light. Slowly I reach up, up, up and put my hand around my head-torch.

CLICK.

And there is light.

One of the worst things about camping in the dark, is how inconspicuous your light is. Like sneezing in a library. All of a sudden, everyone notices you and in these cases, knows where you are. And yet I have little idea of where they are.

The river hushes by and as I stare I realise that what I’m expecting to see is two eyes, green or marble purple shining back at me. What are you doing, this is silly, I think for the eyes see me, but I do not see the eyes. But then why would I? They are not here…at least I don’t see them. But there was something, I know it and now I want to see it, if only to confirm that I was right. And so, one foot follows the other into the jungle, crrrrunch, crrrrack and splodge through mud, leaves and twigs and somewhere the river hushes by. I push branches out of the way as others brush against my bare legs and after barely a few steps I stop, poised…and think and think; no, I decide, if it IS a jaguar….go back, get back in the tent….I turn to look over my shoulder, and the light tunnels through the darkness, but there is no tent, where is the tent?” Panic surges and I hurry back then splodgecrunchcrack, until with relief, there it is, I see it! I get inside, quick-quick, zip the porch, zip the door, zip the sleeping bag and listen, and listen and listen and the river hushes by….Hussssh.

|

| As butterflies go….pretty fancy. |

The birds bark and cackle, squeak and squawk in the morning and I stand staring into the jungle, staring at the noisiest of all of the trees, but not one bird can I spot, not one. It’s always the same, a ragtime cocktail of tunes but I can never see the source. Breakfast company is more visible; long leech-black millipedes and butterflies of orange, pastel green and a beautiful black dart-shaped one. I

|

| One, two, three, four…wait, stop moving fella! |

ride back out along the lovely fast stretch of dips, ruts and whoops, back beneath the trees heavy with mangoes to Buena Vista. From here along the main road to try and find the trail which leads to the park. The morning is a hubbub of life and noise, buying and selling, motos, trucks, pickups and buses loading and unloading people and wares. I’m so preoccupied by the sights and sounds that I miss the turn off and it’s only when I cross the river by huge expanse of bridge that I realise I’ve gone too far. However, now on the far side of the river it crosses my mind that I should just drop off the road onto the dirt and ride to the park directly from here, surely avoiding having to cross the river! The locals must know better though, so I go back and find the turn-off.

A rocky bed scarred with a variety of tire-tracks darting off in many directions. The bed is dry here and piles of wet sand and gravel mark the river’s recent high point. Just beyond the drying detritus is the river, curling around like a thick brown question mark. There are no other bikes nor a canoe, certainly no cars, but there are people crossing by foot, under burdensome loads. I watch them carefully as they cross, using thick sticks to steady themselves against the muddy current, a little less than waist deep and all the while wondering to myself can I cross? The thought disappears as I make the decision, let out the clutch, and the front wheel enters the water. Whilst sandy at the edge I find as I progress that the middle and far side is littered with larger rocks and I buck and dip into hollows deeper than anticipated. Uncontrollably I veer off left but just manage to catch the fall before gladly making it out. As I ride up the riverbank, bags, boots and bike dripping dry, a group of locals chuckle amongst themselves at my recent bucking, seat of the pants, feet off the pegs, ride across. They tell me that passing to left is the better way to take, shallower and smoother. I’ll remember that for when I return. Frustratingly, more locals arrive on motorcycles now, they would have shown me the way had I been a minute later. Some men I notice prefer still to push their bikes, their Chinese machines perhaps more susceptible to the water. I help one culprit with tools and labour to get his bike running though he is completely indifferent to my help and once fixed he sits there all the same, in no rush to continue.

|

| I fixed this bike after he flooded it, the owner is in yellow and clearly in no rush to move. |

|

| You should pass to the left, gringito! |

I leave the men behind to ride on towards Laguna Verde, passing a village with homes of broad wood planks and shaded by frond roofs. There are no road-signs and the route is littered with rivers, many of which I cross twice as I take wrong turns. There are two distinct types of river crossing; slow moving, muddy and soft, or otherwise fast boulder-strewn white waters. The trail thins and thins as I progress until it is just two tyre marks in the tall grass. I love the trail and love the place, until occasionally rounding a bend, the muddy trail drops steeply between the trees and all that I can see ahead is muddy water….and then more trees. And then I don’t like it so much. There’s something about it, just something I don’t like, the narrow field of view, the darkness, a tunnel through the jungle but no light at its end, just a river….Rivers, you just never know until you are safely across. My fear is always of getting stuck half way, either flooding the engine with water or just bogging down in impossibly thick mud and not being able to push out alone. Luckily today I make it each time and then pass a sign which tells me I have entered the national park. This sign however doesn’t seem to deter the locals who – as it is well known – are still burning down swathes of jungle to make way for mandarins, beans and yams. There are few houses now , far from Buena Vista and the trail becomes a footpath then which I ride along until it too peters out, outside the refuge.

|

| Idyllic |

|

| Lovely trail, not too long. |

|

| My guess is that Laguna Verde is in those mountains |

|

| Just don’t like these…and there were quite a few. |

The refuge for chickens. A nice sign states that this is the start of the footpath to Laguna Verde, my target, but I can’t find the path. I find a lot of chickens, and a lot of signs with tree names on them, and a very empty refuge (save for more chickens). There is also a house at the end of a large flat pasture and I walk to it, but find it is deserted too. Amboró is just not working out for me!

I’ve spent five days now just trying to get in to the park! Sometimes you just know. Sometimes you have that feeling that you have to try butthere is also something else in the back of your mind telling you – not so much that you will fail but – that you are just wasting your time. Of course these amount to the same thing, failing and not arriving, but failing to my mind means that you gave up. Sometimes though, it’s futile, you can’t do it no matter how hard you try. And perhaps worse is that you know it…..and yet you still try anyway, then try again, and again. I knew it, I knew it seven days ago sitting in Samaipata as the rain pelted down, before I’d even started. Now there is little else I can try, save for walking randomly off in to the jungle.

I eat an apple and watch photon-beam birds, listen to their bright darting calls and start thinking about trying, luck, skill.

Photon-beam bird:

I used to think that you could do anything and that if you tried, practised and worked extremely hard you could do it, you could do anything. But it’s not quite like that. One day you are dreaming about what you want to be when you grow up, watching these guys on TV whilst you do your homework, or reading about them in books whilst working your crappy part-time job, and then the next day you wake up and think “shit, I’m grown up” and the guys on TV are younger than you. It’s not that I’m old, let’s get that straight, just that a lot of things require you to be kicking some amount of ass at an early age. I’d spent so much time thinking about what I wanted to be that the opportunity -to be something a little bit special – had passed. The world IS full of opportunities but if you (and likely your parents) don’t cotton on to one’s God given opportunity from day one, then it will likely just pass you by. Gone, boom. So, to quote Joe Simpson,

“You gotta make decisions. You gotta keep making decisions, even if they’re wrong decisions, you know. If you don’t make decisions, you’re stuffed.”

Quite right, and whilst Joe decided to try and get out of the huge crevasse he foudn himself in, I decided to get out of Amboro.

Just after setting off back towards Buena Vista I stop at a house not far from the refuge and talk to a man. I wonder what opportunities he has had and missed, what was his gift? He offers to guide me to Laguna Verde himself, but not today, it’s too late, he’ll take me tomorrow. He knows the way well and –sadly for me – he’s no fool and won’t let this opportunity pass him by, must know what the tours are charging and therefore he wants a similar premium. Well, I think, I’ve put so much time in, I can either keep going or quit Amboro, so I make another decision; to pay.

“Yeah OK,” I say, “can I camp here then?”

”Oh, no!”

”No?”

”No, if it rains tonight, you might not be able to get out across the rivers!”

”Mmmm, yeah, OK, well….if it does rain, how long does it take for the rivers to drop?”

”Maybe four months!”

And that was that for Amboró!

|

| A cheeky meal |

|

| A cheeky monkey |

|

| Cheeky chappies |

|

| A cheeky….owl |

|

| Fishing on the Surutu |

So I carry on back to Buena Vista, riding the ten or so rivers a second time and return to my previous night’s camp hoping to see the jaguar! Instead I see a group´of men turn up in a car. It’s dusk, pink and purple and bang bang bang go the doors on the pick up. I poke my head out of the tent and say hello. They are uninterested and disappear down the red mud bank to the river. When I look again, they are walking abreast each other, holding a net across the breadth of the river, trapping the fish as they walk upstream. I notice that it’s not raining and I realise with some sadness that it won’t rain tonight after all. The men return late in darkness and throw their machetes and fishing nets into their pickup, waking me from sleep. Their torches dart over the tent and they chatter. The sound of the beer cans then, psst, psst, psst. Four men with machetes drinking beer outside my tent in a quiet corner of Bolivian jungle. The nocturnal voice in my head says that they could rob everything I own, chop me up and throw me in with the fish, and not a soul would know. I try to stay awake, to be ready, tell myself it’s just evolution keeping me worried at night in order to stay alive, until I tire of the voice and succumb to sleep.

|

| El papa |

I gasp and wake damp with sweat, I’ve slept a little late and the sun is high and burns hot on the tent. Later, as I munch cold porridge and fruit, some local men arrive to gaze at the river. They talk to me about “the men that came to fish,” and tell wild stories of how the fish were abundant, easy to catch, the biggest they’ve ever seen and “swimming so close to their feet that they could catch them with machetes!”

|

| Okinawa square |

Everything packed up, I look at the map to the loop of Jesuit Missionaries out east beyond Santa Cruz. I’d been thinking about these a long time, before I’d entered Bolivia having seen them dotted on the map. Ushuaia will wait. I cut across from Buena Vista on a lesser road, avoiding Santa Cruz, and instead passing through a busy industrial-farming strip, including the Japanese colony of Okinawa. As I progress the route become ominously quiet until the reason for this becomes clear: the Rio Grande.